and synchronized, for use with flash bulbs. I hadn't given it much thought at all months ago when I hooked up a modern electronic flash to one of my Kodak BHF cameras. It didn't take much to get it to fire a flash, so I shot a roll of film expecting all would be well, but it wasn't.

and synchronized, for use with flash bulbs. I hadn't given it much thought at all months ago when I hooked up a modern electronic flash to one of my Kodak BHF cameras. It didn't take much to get it to fire a flash, so I shot a roll of film expecting all would be well, but it wasn't.I abandoned that idea for a while, but then recently gave some more thought to the idea. Of course there is no real reason why I would need to do this since I have plenty modern cameras that are flash ready, but still, I have a sweet spot in my heart for old cameras. After taking apart a BHF, and staring at the shutter mechanism for what seemed like hours, I figured out what it needed. I needed to mechanically alter the timing of the flash striker about 100ms, and that would permit the shutter disc to completely clear the aperture before firing the flash.

This was easy to test too. After making adjustments, I left the back off the camera, placed by eye right up to the camera and fired the shutter. If you do this on an original, you will only see a small amount of ambient light since the flash is firing before the shutter disc is allowing light through the aperture. After making the adjustments though, if you do this same routine, you will get a nice blast of flash!

Okay, fast forward a bit. Having successfully modified a BHF and processed a test roll of film, I was quickly thinking about another camera. I have two Ansco Shur-Flash cameras, and being those are 6x9cm format, why not attempt to modify one of them? So I did just that.

I went through the same basic process with the Ansco as I did with the BHF, and it too now fires the flash at the exact instant the shutter disc has cleared the aperture. In the photos below are the mechanisms of the Ansco Shur-Flash. The key components are circled and are in different colors.

A- Flash conta

ct.

ct.B- Flash sync striker

C- Ramp

D- Flash striker jumper.

I will try to explain the sequence of events to trip the shutter and fire the flash, but seeing is believing. I would recommend opening one up and observing it in action. When the shutter button is depressed, it causes D to move towards C. As D goes up the ramp C. it causes the striker B to be elevated above flash contact A. This is necessary to elevate the striker arm to clear the flash contact because contact is not made until the return stroke. So, when the shutter mechanism cycles, it causes the flash striker arm to travel down to the flash contact, and then return to the rest position seen here.

As seen in the photo to the

left, you can see there is a wide foot that is used to make the actual contact between the striker arm and the flash contact. When the leading edge of the original 'foot' makes contact, the shutter disc is still closed. To complete this modification, it will be necessary to flatten that 'foot' shape to end up with a slightly down turned edge. This will cause the bitter end of the new shape to make contact just as the shutter disc has cleared the aperture. It will take a bit of fuss to get the timing correct for this, but it's not too difficult to accomplish. When making these adjustments it's easy to keep cycling the shutter slowly to see when you have reached the point when the contact is made just as the shutter disc has cleared the aperture.

left, you can see there is a wide foot that is used to make the actual contact between the striker arm and the flash contact. When the leading edge of the original 'foot' makes contact, the shutter disc is still closed. To complete this modification, it will be necessary to flatten that 'foot' shape to end up with a slightly down turned edge. This will cause the bitter end of the new shape to make contact just as the shutter disc has cleared the aperture. It will take a bit of fuss to get the timing correct for this, but it's not too difficult to accomplish. When making these adjustments it's easy to keep cycling the shutter slowly to see when you have reached the point when the contact is made just as the shutter disc has cleared the aperture.

Here are a few photographs made with the BHF I modified for electronic flash.

St. Johns Church. I used a Sunpak 522 to make these exposures as the little flash would not be powerful enough.

One of the more stately markers in the cemetery.

Here's another marker I really like. I also like the way this one was lit up in the background.

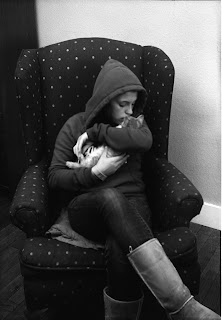

And here is a shot from the Ansco Shur-Flash. This was the only nice shot from that test roll. Evedentally the Ansco has a minimum focus distance of 6' or more. All the shots I took at around 5' were pure fuzz in the foregrounds, but clean at 6' and greater. Note to self...